Airplanes

Introduction

This document provides simple calculations for idealized cases of airplane performance.

Straight and Level Flight

When an airplane’s wings move through the air, they generate a lifting force, “L”, in a direction perpendicular to the wings. For level flight, the lift must equal to the downward force of gravity “W”; as illustrated below [1]:

L

(Lift)

![]()

|

||||

Note that the weight “W”, or force of gravity, is simply the mass “m” of the airplane times the gravitational acceleration “g” which is about [2] 32.174 feet/second2 or 9.807 meter/second2. This relation is expressed as:

L = W = m g (1)

Forces in a Turn

To turn, the aircraft must be tilted or “banked” through some angle “f”. This lift is a vector that can be seperated into vertical and horizontal components.

|

f (bank angle)![]()

|

As the airplane banks, the total lift perpendicular to the wings must be increased so its vertical component still equals the downward force of gravity. To accomplish, this either the wings can be tilted so they strike the oncoming air at a bigger angle, i.e. at a greater “angle of attack”; or power can be applied to increase the speed of the airplane.

The increased lift necessary to maintain level flight is simply

L(increased lift) = W / cos(f) (2)

The horizontal component of lift is equal to the “centripetal” force “Fc“, which is now available to turn the airplane. This force, “Fc“, points to the center of a circle about which the airplane will travel at a uniform speed and is given by

Fc = m V2 / R (3)

where “V” is the forward velocity of the airplane and “R” is the radius of the circular path of the airplane, and “m” is again the mass. For those interested, this relation is derived at the end of this document.

The top view of a turn is shown below:

“centripetal” force forward velocity radius of

turning circle

where “V” is the forward velocity, “R” is the radius of the circle, and “Fc“ is the centripetal force.

Radius of a Turn

Note that the lift is generated perpendicular to the wings. The lift is a vector quantity and can be separated into the vertical and horizontal components as a function of the angle of bank, “f“.

Recalling that the trigonometric tangent is the opposite side divided by the adjacent side of a right triangle, we have

tan( f ) = Fc / W = (m V2 / R) / (m g) (4)

or

R = V2 / [ g tan( f ) ] (5)

where R is the radius of the turning circle, the gravitational acceleration “g” is about 32.174 feet/second2 or 9.807 meter/second2, V is the forward velocity, and the angle of bank “f” could be in degrees or radians. The tangent function is dimensionless.

Rate of Turn

The rate of turn can be expressed using the previous expression for the radius of the circular path. The distance travelled to complete the circle is 2pR (feet/revolution). Note that the final result is only dependent on the bank angle and forward velocity.

Rate of Turn = 360° [ V / (2pR) ] (6)

or eliminating “R” using the equation (5) above, we have

Rate of Turn = (180° g / p) [ tan( f ) / V ] (7)

or

Rate of Turn = C1 [ tan( f ) / V ] (8)

where the constant

C1 = 32.174 (180/p) =1843.4 ( (degree/second) * (feet /second) ) (9)

for V in feet/second

or

C1 = 32.174 (3600/5280) (180/p) = 1256.9 ( (degree/second) * (miles/hour) ) (10)

for V in miles/hour

or

C1 = 9.807 (180/p) = 561.9 ( (degree/second) * (meter/second) ) (11)

for V in meter/second

A table of the rate of turn in degrees/second is given below:

|

Speed |

Rate of Turn (degrees/second) |

|||||

|

mi/hr |

100 |

125 |

150 |

175 |

200 |

|

|

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

|

10 |

2.2 |

1.8 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

|

|

20 |

4.6 |

3.7 |

3.0 |

2.6 |

2.3 |

|

|

Angle |

30 |

7.3 |

5.8 |

4.8 |

4.1 |

3.6 |

|

(degrees) |

40 |

10.5 |

8.4 |

7.0 |

6.0 |

5.3 |

|

50 |

15.0 |

12.0 |

10.0 |

8.6 |

7.5 |

|

|

60 |

21.8 |

17.4 |

14.5 |

12.4 |

10.9 |

|

|

70 |

34.5 |

27.6 |

23.0 |

19.7 |

17.3 |

|

|

80 |

71.3 |

57.0 |

47.5 |

40.7 |

35.6 |

|

G-Loading

As the airplane banks, the pilot needs to increase the lift, perpendicular to the wings, so the vertical component of lift matches the weight; and level flight is maintained. This provides an extra “centripetal” force, equal to the vertical component of lift, which is needed to turn the airplane.

The consequences are that passengers will feel an increased pressure straight down into their seats as if they suddenly became heavier. This increased force or “G-loading” is usually normalized to the usual force of gravity and is defined as

(Increased Lift) = (G-loading) (Original Lift)

Since the original lift “L” was equal to the normal downward force of gravity “W” for level flight we can write

G-loading = (Increased Lift) / W = [ W sec( f ) ] / W (12)

G-loading = sec( f ) = 1 / cos( f ) (13)

Please recall that the trigonometric secant function is the hypotenuse divided by the adjacent side of a right triangle and is the inverse of the cosine function.

A table of the apparent relative increase in the force of gravity is given below

|

|

G-Loading |

|

|

0 |

1.00 |

|

|

10 |

1.02 |

|

|

20 |

1.06 |

|

|

Angle |

30 |

1.15 |

|

(degrees) |

40 |

1.31 |

|

50 |

1.56 |

|

|

60 |

2.00 |

|

|

70 |

2.92 |

|

|

80 |

5.76 |

Standard Rate of Turn

In turning flight, the time for one complete revolution of 360°, i.e. travelling a distance of 2pR, is given by

Time/Revolution = (2pR) / V (14)

or eliminating “R” using the equation (5) above, we have

Time/Revolution = (2p / g ) [ V / tan( f ) ] (15)

or

Time/Revolution = C2 [ V / tan( f ) ] (16)

where the constant

C2 = 2p / 32.174 =0.15929 (second2/feet) (17)

for V in feet/second

or

C2 = (2p / 32.174) (5280/3600) = 0.28642 (hours*seconds/mile) (18)

for V in miles/hour

A table of the times for one complete revolution in a turning circle is as follows:

|

Speed |

Time for One Revolution (360 degrees) in Seconds |

|||||

|

mi/hr |

100 |

125 |

150 |

175 |

200 |

|

|

10 |

162.4 |

203.0 |

243.7 |

284.3 |

324.9 |

|

|

20 |

78.7 |

98.4 |

118.0 |

137.7 |

157.4 |

|

|

Angle |

30 |

49.6 |

62.0 |

74.4 |

86.8 |

99.2 |

|

(degrees) |

40 |

34.1 |

42.7 |

51.2 |

59.7 |

68.3 |

|

50 |

24.0 |

30.0 |

36.1 |

42.1 |

48.1 |

|

|

60 |

16.5 |

20.7 |

24.8 |

28.9 |

33.1 |

|

|

70 |

10.4 |

13.0 |

15.6 |

18.2 |

20.8 |

|

|

80 |

5.1 |

6.3 |

7.6 |

8.8 |

10.1 |

|

In common flight parlance, a “Standard Turn” is one complete revolution of 360° accomplished within two minutes or 120 seconds. The angle of bank, fSTD, needed to accomplish this feat is only dependent on the forward velocity of the airplane. Using equation (14), we get

120 seconds/revolution = (2p / g ) [ V / tan( fSTD ) ] (19)

or

tan( fSTD ) = V [ p / (60 g ) ] (20)

or

fSTD = arctan { V [ p / (60 g ) ] } (21)

or

fSTD = arctan ( V / C3 ) in degrees or radians (22)

where the constant

C3 = 32.174 (60/p) =614.48 (feet /second) for V in feet/second (23)

or

C3 = 32.174 (3600/5280) (60/p) = 418.96 (miles/hour) for V in miles/hour (24)

A table of results is as follows:

|

Speed |

Angle of Bank for Standard Rate Turn in Degrees |

||||

|

mi/hr |

100 |

125 |

150 |

175 |

200 |

|

13.4 |

16.6 |

19.7 |

22.7 |

25.5 |

|

A convenient approximation, or rule of thumb, is that the required angle of bank for a standard turn, is five degrees plus the velocity in miles per hour divided by ten; so for example at 150 miles/hour

fSTD (150 miles/hour) @ 5 + 150/10 = 20 degrees (25)

Pure Sidewise Slip and Terminal Velocity

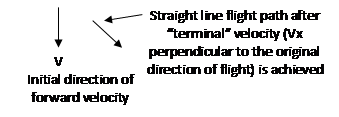

An interesting option is to bank the airplane but apply the rudder to keep the airplane always pointed in the original flight direction.

In this case the airplane will initially accelerate in the direction of the bank because of the force associated with the vertical component of the lift. But, as the drag due to air resistance increases as the square of the sidewise velocity, the two opposing forces will eventually cancel out. When the net sidewise acceleration goes to zero, the airplane will be moving at a constant sidewise “terminal” velocity.

This is illustrated below:

|

Initial

acceleration causing slip in direction of bank

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In this case the “centripetal” force is

![]()

The drag of air resistance is linearly related to the velocity squared as

![]()

where “k” is a constant and “vx“ is the sidewise velocity. The total force is then

![]()

Solving for the sidewise acceleration “ax” which is the first derivative of velocity with respect to time, “t”, we get

![]()

or

![]()

where ![]()

is the “terminal” velocity or the solution of the above equations when ax = 0. Thus we have the greatest sidewise acceleration “ax” and zero velocity “vx” initially at time equal to zero. Then as sidewise velocity increases, so does the air resistance. Eventually the drag force due to air resistance equals the force due to the horizontal lift component and the acceleration becomes zero and the velocity equals the maximum or “terminal” velocity given by “vT” above.

In any event, rearranging the terms we get

![]()

and solving the integrals [4], we have

![]()

or

![]()

where ![]()

Note that the term “![]() is zero at t = 0 and asymptotically

approaches a value of one at large times.

is zero at t = 0 and asymptotically

approaches a value of one at large times.

The air resistance constant, “k” is given as

![]()

For example, for a typical light airplane we have

r = 1.2 kg/m3 is the air density,

A = 20 meter2 is a typical cross sectional area of the fuselage, and

Cd = 0.5 is the corresponding dimensionless “drag coefficient” of the fuselage.

For the same typical light airplane with a mass of about 1000 kg, we get

k = 6.00 (kg/meter)

and

vT

/ sqrt[ tan(![]() ) ] = 40.4 (meters/second)

) ] = 40.4 (meters/second)

C4

/ sqrt[ tan(![]() ) ] = 0.243 (second-1)

) ] = 0.243 (second-1)

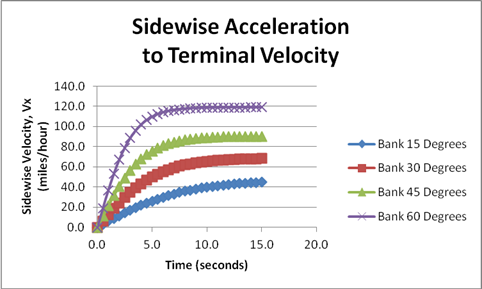

and the following graph

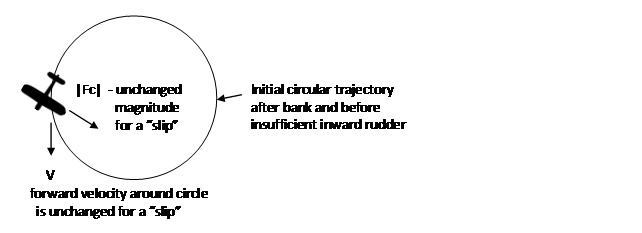

Flight Path of an Uncoordinated Turn

The important thing to remember is that the angle of the bank, and the forward velocity, alone determine the radius of the turning circle and the rate of turn. This is because only “f” and “V” contribute to the inward centripetal force, “Fc”.

The consequence is that, at least initially, the rudder does not cause the airplane to turn but only changes the direction the airplane is pointing in the horizontal plane relative to the forward motion, “V”. Rather the intended purpose of the rudder in a turn is to yaw the airplane so as to cause the horizontal component of lift to continually point to the stationary center of the turning circle. Applying just enough rudder to accomplish this results in a “coordinated” turn.

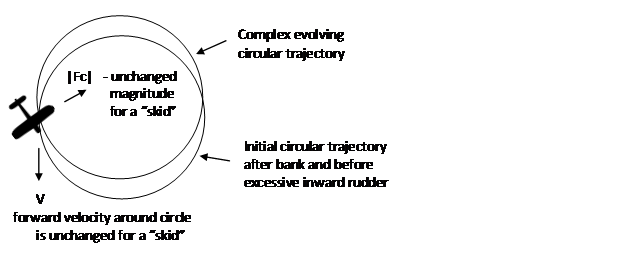

We can then define an uncoordinated turn as the mistake of using too much rudder, via the floor pedals, in the direction of the turn to create a “skid” or too little in the direction of the turn for a “slip”.

Of course an uncoordinated rudder modifies the airplane trajectory more and more as time progresses; but a rigorous mathematical analysis is not generally useful. The reason is twofold; first the analysis is complex; and second the effects are increasingly undesirable, i.e. a potential spin in the case of a skid or a reduction of the turn rate for a slip; both of which are in need of immediate correction.

For a “skid”, the airplane points too much into the turn and the fuselage blocks the airflow to the “inward” wing closest to the center of the circle. Again neither the rate of turn nor the turn radius are different from a “coordinated” turn in which the airplane is not so skewed. The “inward” wing loses lift making the bank angle want to get steeper and increases the chance for a potentially fatal spin.

For a “slip”, too little rudder in the direction of the turn, the airplane is skewed in the opposite direction as shown below. And again the turn parameters are unchanged. In this case the inward wing gains lift with a tendency to reduce the angle of bank thus halting the turn.

In a coordinated turn the forces on passengers are directly down into their seats and there are no annoying sidewise nausea inducing forces. Indeed, it is this feature which the flight panel instrument uses

Piloting a Coordinated Turn

To put the airplane into a coordinated turn, the pilot must perform three separate actions [3].

1. First the wings must be tilted through some angle of bank, f, using the ailerons on the wings. This is accomplished by temporarily turning the wheel, or moving the stick, to the right or left. Note that once a particular bank angle is established, the ailerons should be returned to their neutral position; and in the absence of turbulence, the bank angle will be maintained.

Because of the bank, the lift which is perpendicular to the wings, will have a horizontal component forcing the aircraft sidewise.

2. To maintain level flight, the lift must be increased so that the vertical component of lift still exactly balances the downward force of gravity. This is accomplished by pulling back on the stick to achieve a steady deflection of the elevators on the tail. The net effect is to increase the “angle of attack” of the wings resulting in both increased lift and increased drag. Since the increased drag slows the airplane, the pilot could slightly increase power to maintain a constant forward velocity, “V”.

3. At this point, the horizontal component of lift must be directed inwards toward the center of a circle counterbalancing a “centripetal” force. To accomplish this, the rudder on the tail must have a steady deflection to the right or left to skew the vertical component of lift towards the center of a circle. This pilot controls the sidewise yaw via the rudder using the floor pedals. Again the slowing effects of drag could be counteracted by a slight increased power to maintain a constant forward velocity.

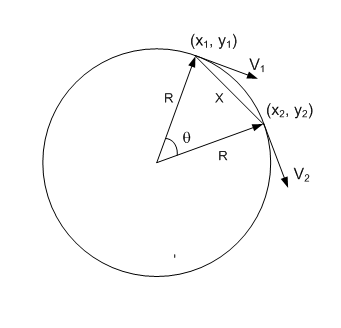

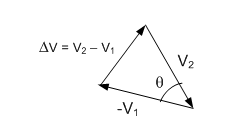

Derivation of Centripetal Force

For circular motion, the magnitude of the velocity is constant but the direction is constantly changing. This equates to acceleration towards the center of the circle. An illustration of this effect is shown below:

where

the velocity vector V1 changes direction some short time later to V2.

The velocity vectors form a triangle which is similar to the triangle formed by the distances of “R” and “X” on the circle above.

Simple Mathematical Derivations

First consider the inverse hyperbolic tangent as follows

![]()

Using the definition of the standard hyperbolic tangent [5], we have

![]()

Solving for the exponential, we have

![]()

And taking the natural logarithm of both sides, gives

![]()

Recalling that ![]() , we have

, we have

![]()

which can be further reduced using

![]()

So that

![]()

or

![]()

Finally, we note the consequences are

![]()

or somewhat more generally,

![]()

References

1. http://www.clker.com/clipart-12023.html

2. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_gravity

3. http://www.rc-airplane-world.com/how-airplanes-fly.html

4. http://www.sosmath.com/tables/integral/integ10/integ10.html

5. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyperbolic_function